Notable Nelson Commissions

Man in Space; 1984, hand carved ultracal pattern, cast in bronze, 1.5x life-size. Commission: Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library and Museum, Dearborn, MI.

Hefty 2-Ply; 1979, hand carved Carrara Statuario Marble, life-size. Commission: Walker Art Center, Minneapolis, MN.

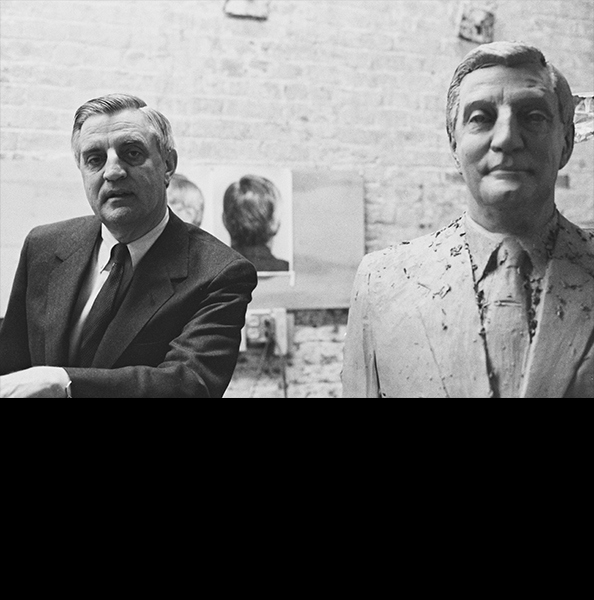

Vice President Walter Mondale; 1982; hand carved, Carrara marble, life-size. Commission: Vice President Mondale for the official bust for the US Capital Building Rotunda, Washington DC

Cheerios; 2007, hand carved, a series of 7, Tamiami Aquifer Caprock marble. Colossal sized, hyper-realistic. Commission: General Mills, Corporate Headquarters grounds installation. Minneapolis, MN.

The following essay, by Martin Friedman, Director of the Walker Art Center from 1961 to 1990 and a key patron to Nelson, is about Nelson’s Man in Space commission. It is a wonderful insight into the creation of public art...

One Small Step For Man, One Giant Leap For Jud

When, in 1976, the Oregon-born sculptor Judson Nelson began fantasizing about carving a heroic astronaut figure, he had no idea that a commission from the Gerald R. Ford Museum in Grand Rapids, Michigan would enable him to realize his dreams.

When the museum was completed, the former president requested that a sculpture commemorating the space program, which he had supported during his congressional service and presidency, be located on its grounds. Because Grand Rapids had already achieved national recognition for commissioning leading American sculptors to create works for its public spaces – major pieces by Alexander Calder, Mark Di Suvero and Robert Morris are encountered by its citizens on a daily basis – why not, reasoned the Ford Museum’s Sculpture Committee, invite another American artist to take on the job of representing the astronaut?

I first become aware of Nelson’s obsessive interest in the subject in 1978 when he was working on an unusual piece commissioned by the Walker Art Center – Hefty Two-Ply, a full-size replica of a plastic garbage bag he was carving in marble. While he admitted that the connection between that lowly, earthbound theme and depicting a space hero was somewhat tenuous,

Nelson presented his case for the astronaut figure with persuasive logic. Underlying his entire sculptural production, he explained, was a compulsion to represent complex surfaces, whatever their origin, in minute detail.

In his translations, even the humblest object assumes nobility. “Carving is my approach to form,” he said. “My work is based on direct observation, line for line, fold for fold.” And now that he had mastered the representation of a plastic sack filled with trash, he decided the next step was to look up – way up. What better way than to carve a man in space?

Nelson, with his large blue eyes, mass of black hair and engaging smile, wearing his customary working outfit – bib overalls that make him look something like Lil Abner – can be extremely persuasive. Interviewed by the sculpture committee and selected for the job,

Nelson began his research with awesome thoroughness. He spent five days at the Johnson Space Center in Houston and befriended by two veterans of the second Skylab Man Mission, Jack Lousma and Alan Bean.

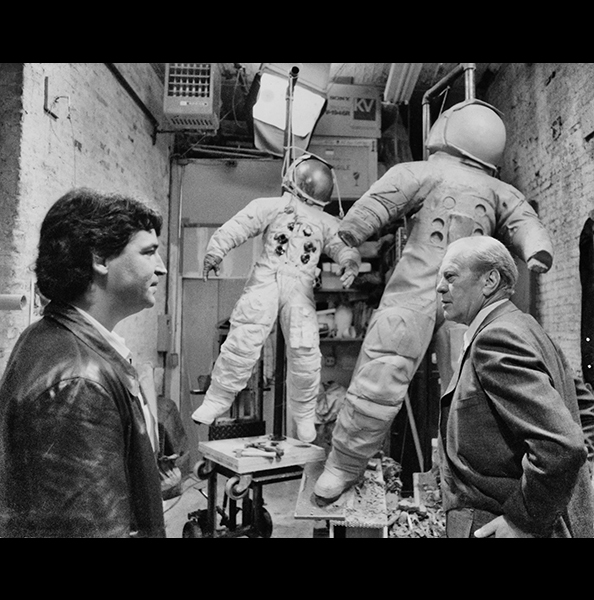

Over tacos with them at the Space Center, Nelson heard what it was like to be weightless high above the earth. When, in September 1982, after an extensive campaign to convince NASA authorities in Houston and Washington of the seriousness of his artistic mission, two gleaming astronaut suits arrived at his Brooklyn studio, Nelson began to reflect on what he had gotten himself into. Unpacked and spread on the floor, the suits, he says, “looked like pancakes I had to bring to life.”

His idea was to create a monumental figure synthesizing elements of suits worn on three historic space missions, Apollo, Skylab, and Space Shuttle.

Despite the futuristic orientation of his subject matter, Nelson set about his task in the methodical manner of a classical sculptor; the first step would be to shape the astronaut in clay.

Two months were devoted to building a complicated armature upon which the borrowed space garb was hung and fussed over so that, he says, “all traces of gravity would be erased.” The final product was not intended to be a line-for-line translation of what was before him.

Because he felt the subject deserved larger-than-life treatment, he decided it should be enlarged by a third; the six-foot astronaut suit became the model for a nine-foot space goliath. It was particularly difficult, he recalls, to make such a scale change and still achieve the feeling of weightlessness.

“The forms and proportions had to be perfect, but above all,” he says, “they had to be my forms and nobody else’s.” The contours and surfaces of the clay were constantly reworked, and the astronaut’s suit, with its seams, folds and flaps, became, under Nelson’s fingers, a gigantic figure scape of buoyant shapes.

For nine months Nelson pinched, sliced and otherwise shaped the clay. After completing the process, he poured gallons of plaster into a rubber mold made from the clay figure. “The clay,” he says, “offered me the form, but it was the plaster that gave me the surface.” Five more months were consumed in refining the contours of the white plaster mass. The next step in this laborious procedure was to make rubber molds from the plaster, into which hot wax was carefully poured. The figure now consisted of twelve parts, the main ones being the helmet, torso, two arms, two legs, and two hands. This third incarnation of Nelson’s astronaut was labored over with the same quiet fanaticism. Each element was then dipped repeatedly into a vat containing a ceramic material that adhered to it, thus encasing it in its own shell.

In the fierce heat of the Johnson Atelier furnace in Mercerville, New Jersey, the wax was melted and the ceramic shells were hardened. The final step was to pour hot molten bronze into the shells. During the next two months the twelve bronze elements resulting from this casting were welded into a seamless whole, and under Nelson’s hammer, chisel and file, were further refined. Ever the hand craftsman, he preferred to take on such complex tasks, normally those of foundry assistant. He lovingly worked over every surface, never allowing any aspect of the sculpture’s development to escape his control. The last stage was the patination of parts of the figure by brushing them with various solutions.

Confronted with the problems of making the astronaut look as though he were floating upward into space and simultaneously anchoring the four-ton mass of bronze to the ground, Nelson’s solution was to create the shuttle’s Extravehicular Activity Hatch through which the astronaut ascends to serve as the sculpture’s base.

Seven bolts attach the figure to its tri-petal bronze womb. The astronaut’s serpentine hose, his umbilical cord to the ship, also serves to hold him aloft. As the figure leans forward, at a seemingly perilous angle, a sense of motion is engendered. It hovers over the viewer who, gazing into the mirror-polish of the facemask, sees his own reflection.

In this work, Nelson has carried the venerable technique of bronze patination to dazzling new extremes.

The astronaut’s white suit has been so burnished to a light, matte finish, that the warm bronze glows through. Strapped around his waist is a marvelous contraption, the mission support system, made of cast aluminum brushed with white patina. The hose connectors from the support system to the figure’s chest are red and blue, and the NASA insignia, like the American flag on his shoulder, is rendered I red, white and blue. The base is a dark mass whose surface varies from deep green to brown.

The astronaut’s gloves are light gray and the fingertips, Nelson points out, are baby blue. During the period when the sculpture was being installed on its concrete pad outside the museum, says Nelson,

“I watched at least a hundred people walk up to the figure and run their hands over the uniform. They couldn’t believe it wasn’t real cloth.”

While he is not a space buff, nor has he followed successive launchings with more than casual interest, Nelson is nevertheless greatly intrigued by the spectacle of man floating effortlessly miles above the earth.

In the history of art, he points out, there are relatively few levitating figures, aside from angels and other divinely directed types found in religious paintings and sculptures. Escape from the tyranny of gravity needed to be considered in modern terms – precisely why the astronaut subject made such sense to him.

His spaceman – arms and legs akimbo – “would be a total failure as a standing sculpture, “ he says, but in the context of rising from the capsule hatch into the upper atmosphere, it assumes an eerie grace.

The massive figure is a remarkable synthesis of human and mechanical attributes; in Nelson’s heroic conception, the separation between the astronaut his life-preserving shell is imperceptible.

He considers his sculpture to be as much a monument to the genius of the anonymous thousands who engineered such adventures in space as to the pioneer group of Americans who having donned the magic suit, were able to float in this limitless domain.

Man in Space; Monograph,

Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library and Museum

Martin Friedman

Director, Walker Art Center, Minneapolis

Walker Art Center